The 250 page pre-reading for my first Ed course can be summed up in a Haiku:

“Teaching is for girls”

They said in 1830

Felt infer’ior since.

If you’ll forgive the syllable-cheating, that’s a decent overview. Ellen Condliffe Lagemann’s, An Elusive Science: The Troubling History of Education Research was a fascinating read, obviously much deeper than my haiku attempt, and was also, well, troubling.

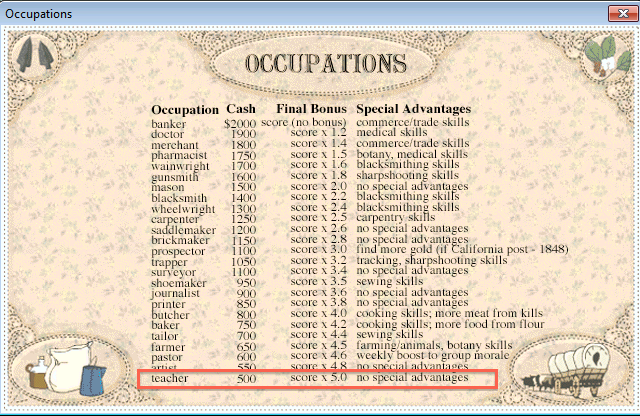

One major issue popped up—as I ineptly haiku-ed—around 1830 when ever-economical schoolmasters realized they could pay female teachers far less than men. Society also rationalized that women educating young ‘ins was a more “natural” state of things. Thus, education came to be viewed as “women’s work” and subsequently—as was the unfortunate perception of many things feminine at the time—of lesser value.

Unfortunately (and perhaps unsurprisingly), times may not have not changed much. Last Sunday, the New York Times ran an article asking “Why Don’t More Men Go Into Teaching?” which the author seemed to believe was a cyclical problem: Apparently men don’t go into teaching because men don’t go into teaching:

“We’re not beyond having a cultural devaluation of women’s work,” said Philip N. Cohen, a sociologist at the University of Maryland. “So that if a job is done primarily by women, people tend to believe it has less value.”

This seems to suggest that if more men simply did it, the field would be raised in stature.

Aside from leaving a bad taste on my fingertips just writing it, would this actually have an effect? I’ve spoken to quite a few male teachers who, in their social lives or especially on the dating scene, feel the need to compensate for their occupation of “just a teacher,” qualifying it with statements like “but I have plans to go into administration.” (I don’t know as many male nurses, but have heard there are similar issues).

Aside from being a sign that you’re on a bad date or need better friends, this seems to indicate that arbitrarily pouring more men into the profession would not address the root of the issue. So what is the root of the issue? Is it:

A) Our devaluation of teaching

B) Continued devaluation of work done by women

C) Associating certain jobs with certain genders

Or a combination of the above? Unlike the NYT, I don’t think it’s clear that one of these factors is necessarily causing the others. What I DO know is that, as I read Lagemann’s book, it became clear that the education field suffers from an inferiority complex, leading it to emphasize heavy handed empiricism in an effort to legitimize itself.

…which we’ll delve into in later posts.

For now, I’m interested in what people think about the idea of teaching as “women’s work” and what this means for education or society in general. Is there a better way to raise the stature of the field than simply recruiting more men? Would that even have an effect? How do we achieve the concurrent goals of valuing teaching as a profession and making the field more attractive to qualified individuals of BOTH genders at the same time?

~C.B.

Feel free to comment below or on the blog’s Facebook Page.

Chris, I’m about 130 pages into “The Teacher Wars: A History of America’s Most Embattled Profession,” by Dana Goldstein. She gives a fine accounting of the gender bias and feminization of teaching through the decades. In her recounting there’s a long history of men giving preference to men and undercutting women any chance they got. Today we’d like to think any professional advances for educators would benefit both genders equally. But given the wide disparities in funding for school systems and other local factors it’s hard to be sure that would always be the case. Discrimination in the U.S. of any sort seems slow to die.

Thanks Kenny – I’ll have to get ahold of that book one of these days!

I can only speak from personal experience. Especially in high school, I definitely had as many if not more male teachers than female teachers. For me, teaching was never something that I considered inferior to other professions. In fact, I always thought of it as a very important one. I’ve just never had any interest in doing it.